Li He / Li Ho

A thousand miles of moonlight

'Cirrus Minor' is a strangely affecting song that begins with a long segment of birdsong before moving into a quiet guitar section. The lyrics when they come are a strange journey (supposedly a drug experience), from a natural but eerie scene of greenery and water to the sun, the moon, and Cirrus Minor. It ends with a haunting organ piece.

One line in the lyrics, 'A thousand miles of moonlight later', is from Li He's poem 'On the Frontier'.

In the introduction to the Poems of the Late T'ang, A. C. Graham takes this poem as an example of the relative ease with which concrete images in Chinese can be transferred into English.

![]() Who was Li He /

Li Ho?

Who was Li He /

Li Ho?

ON THE FRONTIER

A Tartar horn tugs at the north wind,

Thistle Gate shines whiter than the stream.

The sky swallows the road to Kokonor.

On the Great Wall, a thousand miles of moonlight.The dew comes down, the banners drizzle,

Cold bronze rings the watches of the night.

The nomads' armour meshes serpents' scales.

Horses neigh, Evergreen Mound's champed white.In the still of autumn see the Pleiades.

Far out on the sands, danger in the furze.

North of their tents is surely the sky's end

Where the sound of the river streams beyond the border.

| ON THE FRONTIER | 塞下曲 sài xià qǔ frontier under (=under the frontier) song |

| A Tartar horn tugs at the north wind, | 胡角引北風 hú jiǎo yǐn běi fēng northern-barbarian horn pull north wind |

| Thistle Gate shines whiter than the stream. | 薊門白於水 jìmén bái yú shuǐ thistle gate white than water |

| The sky swallows the road to Kokonor. | 天含青海道 tiān hán Qīnghǎi dào sky hold-in-mouth Qinghai road |

| On the Great Wall, a thousand miles of moonlight. | 城頭月千里 chéng toú yuè qiān lǐ wall top moon thousand mile |

| The dew comes down, the banners drizzle, | 露下旗濛濛 lù xià qí méngméng dew come-down flag drizzle |

| Cold bronze rings the watches of the night. | 寒金鳴夜刻 hán jīn míng yè kè cold metal sound night watch |

| The nomads' armour meshes serpents' scales. | 蕃甲鎖蛇鱗 fān jiǎ suǒ shé lín barbarian armour lock snake scale |

| Horses neigh, Evergreen Mound's champed white. | 馬嘶青塚白 mǎ sī qīng zhǒng bái horse neigh green grave-mound white |

| In the still of autumn see the Pleiades. | 秋靜見旄頭 qiū jìng jiàn máotóu autumn quiet see yak-tail-flag top |

| Far out on the sands, danger in the furze. | 沙遠席羈愁 shā yuǎn xí jī chóu sand far mat/seat bridle anxious |

| North of their tents is surely the sky's end | 帳北天應盡 zhàng běi tiān yīng jìn tent north sky must end |

| Where the sound of the river streams beyond the border. | 河聲出塞流 hé shēng chū sài liú river sound issue frontier flow |

The term 塞 sài refers to the northern frontier beyond which the nomadic peoples lived. For the Chinese this was a military frontier. Tang-dynasty poets including Lu Lun, Li Yi, Wang Changling, and most famously Li Bai, had written poems entitled 塞下曲 sài-xià qǔ 'Beyond the Border Tunes', mainly dealing with military deeds and the harshness of military life.

But there are no heroics in Li He's poem, which is an atmospheric piece filled with gloom and menace. It opens with a reference to the horns blown by the hu (胡 hú), a traditional name for peoples to the north and northwest of China which Graham translates as 'Tartar'. This is anachronistic — the Tartars came later in English — but so is Li He's usage. By the time of the Tang the term 胡 had come to refer to the people along the Silk Road. Using it for the Xiongnu harks back many centuries to the time of the Han dynasty.

The Xiongnu or Hunnu dominated the Chinese historical imagination of the northern frontier. From the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD, they held sway over a huge empire centred on modern Mongolia. During this time they posed a continuing if fluctuating threat to China. The Great Wall (referred to in the poem) formed the boundary between China and the Xiongnu.At that time the Chinese had often sent princesses to marry Xiongnu leaders in an appeasement policy known as heqin (marriage alliance). In an episode that has been celebrated ever since, Emperor Yuan of the Western Han dynasty gave five court ladies (not princesses) to the Chinese-backed Xiongnu leader, Huhanye Chanyu, at a time when the power of the Xiongnu was already waning. One of these women, called Wang Zhaojun, married Huanyehe and bore him at least two sons and a daughter. After his death, she married his successor (under levirate marriage) and bore him two daughters.

By the time of Li He, these 800-year old events had been considerably embellished and romanticised. Wang Zhaojun (who later came to be included in the Four Beauties of ancient China) was depicted as a court lady chosen to be presented to Huhanye Chanyu to satisfy his demand for "a princess". Although supposedly stunningly beautiful, she was chosen on the basis of an unflattering portrait painted by a corrupt court painter to whom she refused to pay a bribe. When the Emperor saw her in the flesh he was mortified but had no choice but to go ahead with his decision. In this version, Wang Zhaojun was homesick for China and eventually committed suicide when ordered to remain with the Xiongnu and marry her own son (as her husband's successor) after her husband's death. (In later centuries this story was further embellished so that Wang Zhaojun committed suicide en route to the land of the Xiongnu.)

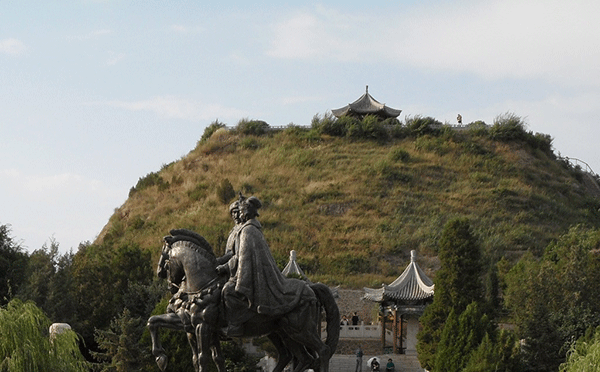

Wang Zhaojun was buried in 青塚 qīng zhǒng 'green mound', so called because it alone remained green among the white and withered grasses of the steppes. This mound makes its appearance in Graham's translation under the name 'Evergreen Mound'. While the actual location of the tomb is unknown, a mound south of Hohhot in Inner Mongolia is now conventionally regarded as Wang Zhaojun's tomb. In Li He's interpretation, the tumulus has already turned an ominous white, like the surrounding grasslands.

The Thistle Gate is a reference to the 薊 Jì area, which in ancient times was situated in northern Tianjin, northeast of present-day Beijing. (There was also a place called 薊門 Jìmén 'Thistle Gate' in the northwest of Beijing and the city still has a major flyover called 薊門橋 Jìmén-qiáo 'Jimen bridge'.)

Qinghai (青海 qīng hǎi 'blue sea') is a large salt-water lake now located in China's Qinghai province. The area has traditionally been an ethnic melting pot; in modern times its ethnicities include Han, Tibetans, Hui, Tu, Mongols, and Salars. In Li He's time it was outside the familiar Chinese heartland and it appears that the road to Qinghai is mentioned for its exotic overtones. Graham renders this with an older English name for the lake, Kokonor, which is based on the Mongolian name Хөх нуур khökh nuur 'dark-blue lake'. In English the name Kokonor arguably has greater poetic resonance than the Chinese name Qinghai, thus highlighting the feeling of exoticism.

The 旄 máo refers to yak-tail, and also to a kind of ancient flag, decorated with yak tail at the top. This kind of flag was a symbol of authority among ancient nomads. However, the term 旄頭 máotóu (mao head) referred to the Pleiades. The modern name is 昴 mǎo. As Graham points out, the flickering of the Pleiades was an omen of invasion by the northern barbarians.

Modern Mongolian-style yak-tail banners (photo from Paul's Travellog)

The tenth line is subject to a number of interpretations. Graham has chosen an interpretation which analyses 席羈 xíjī ('seat bridle') as a type of plant.

I think it doubtful that Li He ever visited these northern borderlands and it is probably more appropriate to describe this poem as an imaginative pastiche of atmospheric images than as a reflection of personal experience.

David Hinton's rendition of the poem is as follows:

BORDERLAND SONG

Mongol horns stretch north wind longer.

Thistle Gate plain glistens clear as water.Sky swallows the road to Azure-Deep Seas,

Great Wall a thousand miles of moonlight,and dew drifting, misting over our flags,

cold metal calls the quarter hour all night.Tribal armor intricate as serpent scales,

horses calling out, Ever-Grass Tomb bare,we watch Banner-Tip stars. Autumn quiet.

Far reaches of sand this grief of distantwandering. Sky ending north of our tents.

Gone beyond borderlands, river-murmurs.