The Significance of Pink Floyd's Allusions to Chinese Poetry

The significance of Roger Waters' allusions to Chinese poetry should not be overestimated. It would be a mistake to compare him to T. S. Eliot, who tapped into the Western literary tradition to add depth and resonance to his poetry. Pink Floyd doesn't exactly reverberate with thousands of years of Chinese poetry. It would be safer to say that Roger Waters simply fancied some of the lines he found in Poems of the Late T'ang and decided to use them in his lyrics.

That said, it's interesting to take a closer look at some of these allusions in the light of the later development of Roger Waters' work.

Themes and Images

The Wall: In 'Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun', Waters used the borrowed lines 'Witness the man who raves at the wall / Making the shape of his questions to Heaven'.

The source was 'Don't Go Out of the Door' by Li He (Li Ho), a poem which concludes with the line (in translation) 'Witness the man who raved at the wall as he wrote his questions to Heaven'. Waters takes his entire two lines from the Chinese poet.

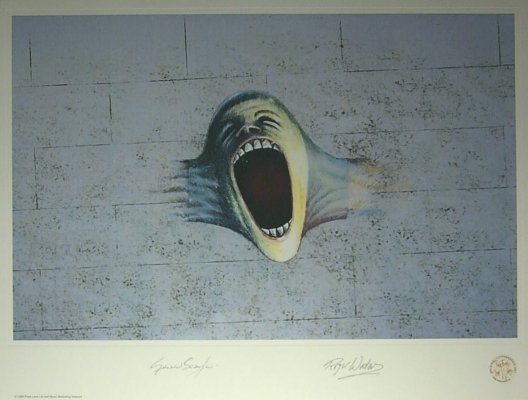

The use of these lines is highly interesting, because the wall is the dominant image and metaphor in one of Pink Floyd's later and most important albums, The Wall. But the image of the wall that re-emerges undergoes a fundamental change. The original wall in Li He's poem suggested an impenetrable, inscrutable barrier that was imposed by outside forces, presumably the 'heaven' that the man is questioning. In The Wall, it is a psychological and emotional barrier against the world found in the heart of each person. This wall has been built up by people to protect themselves but ironically becomes a symbol of alienation, in Waters' case alienation from his fans and society in general. While the nature of the wall is changed, the palpable sense of frustration engendered by it remains and has, if anything, become stronger.

It is remarkable that the seed for the concept behind one of the best-selling rock albums of the late 20th century may have been planted by a Chinese poem from over a thousand years ago.

Love: The poetry of Li Shangyin, languishing and romantic, could not be further removed from the cynical, existential lyrics of Pink Floyd, which feature very few love songs in a conventional sense. Nevertheless, there must have been something about Li Shangyin's poetry that attracted the young Roger Waters, not least the Chinese poet's beautifully expressed anguish, despair, and (should we say it?) self-pity. Knowing the source of the lyrics gives a whole new dimension to the seemingly harmless pastoral images of the first verse of 'Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun' -- in particular, the trembling leaves and resting swallows.

The attraction exerted on Waters by Li Shangyin's poetry may partly be due to Graham's translation. In his preface to the Poems of the Late T'ang Graham points out that in English translations of Chinese poetry, the style of the translator tends to override that of the original poet. Graham's own translations of Li Shangyin tend to be harder and sharper than those of other translators, some of which are soft and 'poetic'. Perhaps it was Graham's style, rather than that of Li Shangyin himself, that affected the young Waters.

That said, the poetry of Li Shangyin does more than contribute a few images and atmospherics to Floyd's lyrics. There is one image in 'Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun' that is central to Roger Waters' later work.

When Li Shangyin wrote 'One inch of love is an inch of ashes', he was giving voice to the despair and disappointment of love -- a potent line in both Chinese and English, but at the end of the day a straightforward expression of thwarted love. By altering the line to 'One inch of love is one inch of shadow', Waters completely transforms Li Shangyin's original intent into something almost sinister. Taken in conjunction with the line that follows, 'love is the shadow that ripens the vine', Water's observation on love is reminiscent of the darker poetry of William Blake. The deepest and most important human emotions are not the wholesome elements they purport to be, but a dark and insidious source of unhappiness. What kind of fruit would be ripened by such a love? When he ends 'Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun' with the question, 'Knowing the sun will fall in the evening, / Will he remember the lessons of giving?', was Waters groping for an early answer to the selfishness of love?

In Waters' later work, this dark view of love grows almost into an obsession. The Wall is Waters' indictment of those whose love is most important and valuable to us (mother, teacher, and wife) yet who cruelly betray us by forcing compliance with the sick system and its values. It's Mother who says: 'Hush now baby don't you cry / Mama's gonna make all of your nightmares come true / Mama's gonna put all of her fears into you.' It's also clear that Waters found this darkness deep within himself, timidly asking ('The Final Cut'):

..If I show you my dark side

Will you still hold me tonight.

And if I open my heart to you

And show you my weak side

What would you do?

Would you sell your story to Rolling Stone?

Would you take the children away

And leave me all alone,

And smile in reassurance

As you whisper down the phone?

Would you send me packing

Or would you take me home?

Disgruntlement: Anyone following Waters' lyrics will notice that they start out light enough in tone but assume an increasingly depressing cast as the years go on. What is interesting is that Waters was already attracted at this early stage to such a figure of pessimism as Li He (Li Ho), whose work brims with dissatisfaction and depression. It's almost as though Waters had found a kindred soul in the Chinese poet. Indirectly, Li He's depression leads us even further back, to Qu Yuan (Ch'ü Yüan), a tragic figure who despaired at the state of his country.

Indeed, there is an uncanny similarity among these three poets (if Roger Waters may be so called) whose lives are each separated by over a thousand years. Despite differences in the subject of their lament, all three were deeply unhappy with the society of their times.

Qu Yuan (Ch'ü Yüan) lamented that his country was being destroyed by gullible rulers and conniving politicians. His complaint is seen as a justified one by the Chinese, who honour him as the epitome of selfless patriotism. Even today, his name is invoked in patriotic appeals to sacrifice personal interests to those of the nation.

Li He (Li Ho) liked to compare himself to Qu Yuan and other great men of antiquity, regarding himself as a person transcending the common run. Embittered by the fact that jealousy and bureaucracy deprived him of the opportunities to which his abilities entitled him, Li He's poetry expressed an intense dissatisfaction with the unfairness of society. But unlike Qu Yuan, his despair is rooted less in the state of the country than in his own personal circumstances — a personal tragedy, not a national one. Li He had something of a chip on his shoulder against the world.

Coming down to our own frustrated and unhappy era, we find Roger Waters angry with everyone and everything — the politicians who betray England and its people, the dictators who are leading the world to destruction, the exploitative system that causes alienation and destroys human respect, and the complicity of even the closest human relationships in the oppressive web. The root of Waters' darkness seems to have been personal — the death of his father in World War II — but Waters saw this as a result of betrayal by the system and turned his bitterness against society. As time went on, this became more and more pronounced, from the 'quiet desperation' of Dark Side of the Moon to the cynicism of Wish You Were Here and Animals, to the deep-seated rage (almost 'paranoid fury') of The Wall and The Final Cut. While much of this bitterness was of a personal nature, it appealed to baby boomers' sensibilities enough to make it an expression of the entire era in which it was produced.

Other themes

There are several other themes that Roger Water's lyrics share with Poems of the Late T'ang, although any connection can only be speculative as there are only one or two direct allusions.

Sun, Moon, and Stars: There are many references to heavenly bodies in Poems of the Late T'ang, especially in the verse of Li Shangyin and Li He. The line 'A thousand miles of moonlight' (from 'Cirrus Minor') is lifted directly from Li He. Although very few specific allusions are found in Roger Waters' lyrics, one wonders whether the recurring imagery of the moon and the stars in the Graham anthology might not have dovetailed nicely with Pink Floyd's early predilection for astronomical and space images, including 'Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun' itself.

The symbolism of the sun and the moon was developed further in The Dark Side of the Moon, where both the sun and (especially) the moon play a key role in the album's meaning. The opposition between the two shows an interesting parallel with the Chinese philosophy of yin and yang, the moon representing the yin (feminine, passive, dark element) and the sun representing the yang (the masculine, active, bright element). And of great interest is the fact that Poems of the Late T'ang has one poem entitled 'The Eclipse of the Moon'. Coincidence?

Time: In his younger days, Roger Waters appears to have suffered from an exaggerated phobia of the passing of time and growing old. (There is apparently a medical name for this mild form of neurosis, but it escapes me at the moment.) On Obscured by Clouds, he sings 'There's a chill wind blowing in my soul and I think I'm growing old' ('Wot's ... Uh the Deal'). In Dark Side of the Moon the prematurely old Waters frets that 'No one told you when to run, you missed the starting gun / ... The sun is the same in a relative way, but you're older / Shorter of breath and one day closer to death' ('Time'). Li He's poetry and, indeed, much Chinese poetry deals with the passage of time (e.g., 'Up in Heaven'), expressing sentiments that are surprisingly close to some of Waters' lyrics. A few lines from several different poets:

Through how many funerals of the blessed in heaven

The clock's drip-drip sounds on without a pause! ('The Watchman's Drum in the Street of Officials')If heaven too had passions even heaven would grow old ('A Bronze Immortal takes Leave of Han' — the entire poem is suffused with the melancholy of past eras)

The empty shine streams on into the distance,

The bronze pillars melt away with the years ('On and on for ever')And he tethered the sun on a long rope that youth might never pass ('The Liang Terrace')

See how autumn eyebrows have changed to new green.

Why all that thrusting and shoving when we were twenty? ('Sing Loud')Less than a day in paradise,

And a thousand years have passed among men. ('The Stones where the Haft Rotted')Mere chance that the patterned lute has fifty strings,

String and fret, one by one, recall the blossoming years ('The Patterned Lute')

The above hints and parallels make for fascinating speculation, but in the final analysis they should perhaps be taken with a healthy grain of salt. We can never really know what went on in Roger Waters' mind as he wrote his lyrics and conceived the ideas for his albums. These ancient Chinese poems can only give us tantalising clues to some of the influences at work on the young musician. It is a tribute to the peculiar depth and fascination of Roger Waters' vision that the attempt should prove so rewarding.