1. What is Switch-Reference?

The first linguist to put forward Switch-Reference (SR) as a linguistic phenomenon was William Jacobsen, Jr.

In his 1967 paper Switch-reference in Hokan-Coahuiltecan, Jacobsen defined Switch-Reference as occurring when

“a switch in subject or agent … is obligatorily indicated in certain situations by a morpheme, usually suffixed, which may or may not carry other meanings in addition.”

Essentially, the term 'Switch-Reference' refers to an instruction — like a computer instruction such as "Execute script" — whereby a small marker issues an instruction that the referent (i.e., entity being referred to, such as subject or agent) is to be changed.

Jacobsen drew most of his examples from the North American language Washo, in which the suffix/infix -š is used to indicate a switch of subject between two clauses.

In the following sentence, -ida (an 'adverbalising suffix') expresses an action conjoined to that of the main clause. This is indicated in the English gloss (given below) as 'and'. The suffix -ida is unmarked for switching; therefore the same actor ('they') is the subject of both parts:

They-opened-the-door-and they-looked-inside.

The "switch" form of -ida is -išda, as in the following sentence, which features a switch between 'she' as the subject of the first clause and 'you' as the subject of the second:

When-she-is-urinating-SWITCH you-go-inside

Jacobsen noted that some languages have two types of suffix: one to indicate a switch of subject, another to indicate retention of the same subject, i.e., no switch.

He also noted the theoretical existence of a third type, one having a symbol indicating retention but none for switch. Switch in such a language would be implied by the lack of a symbol for retention.

In subsequent years linguists found many more languages with phenomena identifiable as SR. These had a geographical spread from North and South America to Papua New Guinea, Australia, the Caucasus, and Ethiopia. The concrete manifestations of SR seemed to differ from region to region, leading to broadened definitions, awareness of distinctions among different types, and new theoretical questions about its nature. (For details, see Van Rijk 2016 and Ross 2016)

Recently, Northeast Asia has emerged as another locus of SR, notably through Mark Schmalz’s work on Tundra Yukaghir and Dejan Matić’s on Ėven. By 2016, Rik van Gijn, was writing optimistically that:

To our knowledge, there is no overview of SR structures in Northeastern Eurasia, so the overview that we can give here is particularly incomplete. … It is unclear what the geographical extent of this area is, but it is potentially enormous, as converbs in eastern Eurasia are common in many different families (Mongolic, Tungusic, Yukaghir, Nivx, Chukot, Korean, Turkic), although it is not known — at least to us — to what extent these different converbal systems can be described in terms of SR systems… Hopefully a (team of) areal specialist(s) will take up the challenge to describe the converbs of these families so that we achieve a clearer picture of the extent and internal cohesion of this potential SR area.

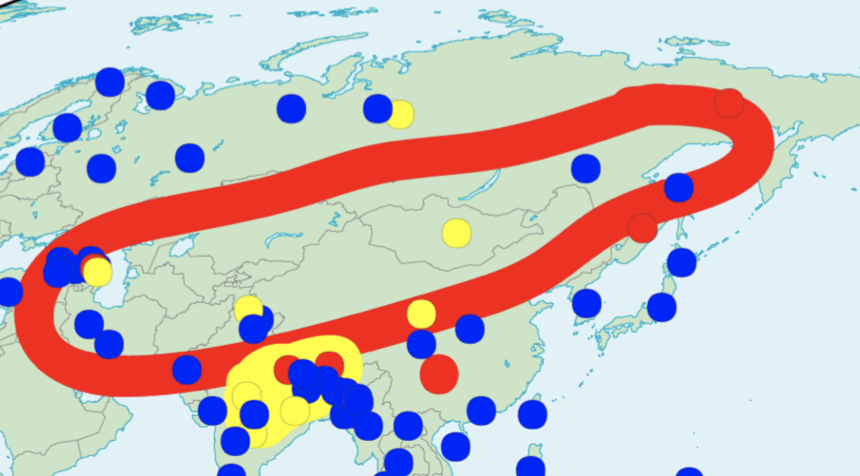

Also in 2016, Daniel Ross identified a belt from Siberia to the Middle East as a potential area for SR. His map included Mongolian as a language having “borderline SR”.

In this post I would like to demonstrate that Mongolian, while not manifesting SR across all domains of clausal syntax, is more than a borderline case. Large areas of Mongolian syntax are unequivocably SR in terms of Jacobsen’s definition.

1. What is Switch-Reference?

2. Outline of Switch-Reference in Mongolian

3. Possessive Forms in Mongolian; their role in SR

- 4.1. Verb Forms that take Case Endings

4.2. Daughter clauses

4.3. Other Predicate Forms

4.4. Gedeg (Complementiser)

5. SR in Ad-subordinate (Adverbial) Clauses

6. Ad-subordinate Clauses with Postpositions

- 6.1. The reflexive attaches directly to the postposition

6.2 The reflexive suffix attaches to the verb form preceding the postposition

7. Verbs that Block the Reflexive Suffix

10. The Subject in Subordinate Clauses

- 10.1.1. Same subject

10.1.2. Different subject (differential subject marking)

10.2. Interpreting the Subject